“We have too many meetings!” – every single employee working in corporate said.

Having meetings that are booked over other meetings three times over is a common challenge for many of us. And it always feels like you’re just stuck in useless meetings and never get a chance to do the actual work.

Creative workers, such as developers, for example, are especially affected due to the nature of their work.

So, in this video I want to share some rules you can follow to make every meeting count, first, and also get rid of unproductive meetings without negatively impacting team performance.

Of course, I have to segway into Scrum a little bit beforehand, since “too many meetings” is one of the most common complaints about Scrum.

The framework was designed in a way that every mandatory meeting, of which there are only 4, has a very specific purpose and a timebox that the team should never go over.

If the team can’t achieve the purpose of the meeting and the timebox expired, the meeting must end. The team then should discuss how to make the next meeting more productive and achieve the goal within the timebox. The team shouldn’t just randomly create other meetings to fill in the gap they created by running the mandatory meetings unproductively.

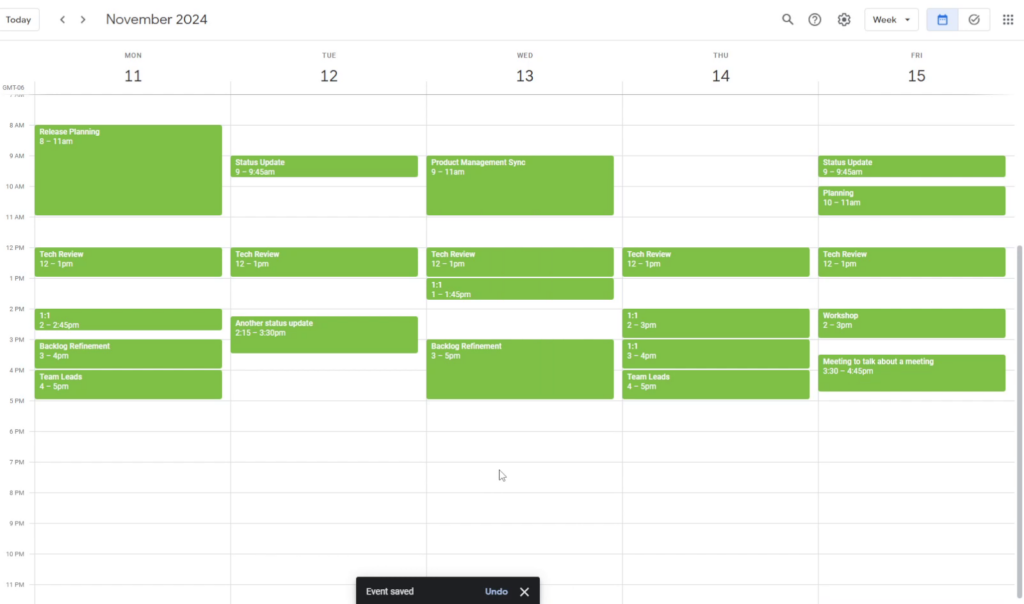

So what I often see when digging deeper into the Scrum teams’ schedules is that most of the meetings they have are not prescribed by Scrum. I see things like Release Planning Meeting, Tech Review Meeting, Status Update, three types of Backlog Refinements, product management meeting, team lead meeting, company meetings, etc.

If you run the four prescribed Scrum meetings effectively, you won’t need any other meetings.

In the end, it doesn’t matter what process or framework you use. To have less useless meetings, you need to improve the key meetings you absolutely have-to-have.

Tell me: how many of you or the teams you work with discuss how to improve meetings that feel unproductive? with actionable steps? and a post-mortem at the end?

That was a rhetorical question, of course.

If you don’t wanna be stuck in useless meetings, you gotta do some work yourself, whether you are a team leader or a team member, a project manager or a developer.

I have FOUR rules for you to follow to eliminate useless meetings.

I specifically use the word “rules” here. Not just ideas, or suggestions. Rules. Because I believe that if you skip any of these five, you probably are not going to see enough improvement. Anyway….

Rule number ONE: a meeting can only happen if it has a clear purpose

Go look at your calendar right now, open up each meeting, and note how many of them have an actual agenda. I bet, most of them are empty or have a copy-paste agenda that was created months ago and is no longer relevant.

With rule number one, you must make sure that any meeting you have in your calendar or you send out has a clearly documented purpose. Think of it as a user story for your meeting. Or for the sake of this video, we’ll call it an attendee story.

In this part, I’m going to deep dive into how to create an attendee story for every meeting because it’s the first rule to follow and until you get THIS right, you should not proceed. This part will also be the longest of this video.

Firstly, it’s not just about having an agenda.

In the rule is said “clear purpose”, not “agenda”. Because I believe that the word agenda is quite often overused or misused when it comes to running meetings.

Most of the time it’s just a list of topics to discuss, and it tends to be very generic or vague. Or it’s an step-by-step of the meeting that is more created for the meeting facilitator, than for the audience.

That’s good and all, and I’d say is an absolute minimum to having ANY meeting. But that’s actually not enough.

A good clear purpose, or attendee story, must have four key elements: the why, the what, the who, and the how.

The WHY.

You need to have a very good reason for having your meeting, a clear “why this meeting is necessary”. This one is a big one because it helps you figure out whether you even need a meeting in the first place.

Think of questions like: Why is this meeting important? Why does it have to be a meeting? And why does it have to happen now?

Make sure your Why is good enough to warrant a meeting and ask some additional questions to help you with that, such as:

What negative consequences would occur, if this meeting doesn’t happen at all? Can we achieve the same purpose in any other way than having this meeting? Is there a better way?

With that why in mind you can define a clear purpose of the meeting, the single goal you want to achieve by the end of it.

For example, the goal of a Sprint Planning is to create and agree on a plan for work to be performed in the upcoming Sprint. It must happen at the beginning of the Sprint because this is when the most recent information is available about what’s most important. If the meeting doesn’t happen, the team will start working in disarray, will lose a lot of time figuring out what to do, and will not be able to deliver the highest possible value to the customer.

This brings us to the WHAT.

What is the expected output of the meeting?

Think of what you’d like to happen by the end of the meeting to be able to say that everyone’s time was used wisely. Generally, it is some kind of artifact, the more tangible you can make it, the better (hint: rule number three should help with that – keep it in mind for now).

To be able to identify a good WHAT of your meeting, you should use active words like ‘create’ or ‘decide’, and avoid words like ‘discuss’ or ‘share’.

In my previous example for the Sprint Planning, I said that the purpose is to create and agree on a plan for work to be performed in the upcoming Sprint. The artifacts created during the meeting are the Sprint Goal and the Sprint Backlog, with broken down tasks that allow the team to start Sprint work right away.

This brings us to the next key element of an attendee story: The WHO.

Think about who must be in the meeting to achieve the purpose and how you expect them to contribute. And be as specific as possible.

For every person you want to attend, thing why they should.

This translates into clearly defining how each person you invite should contribute or what they are supposed to get out of the meeting.

Obviously, you want to encourage transparency and don’t want to have people feel left out. So you can definitely have optional attendees. But even for optional attendees you need to be clear about what you’d expect from them and what king of benefit it is to them to attend (instead of waiting for a summary email, for example).

And when you think about how you’d like people to contribute, it can’t be just ‘share expertise’. Think of a more active action. Like, for our Sprint Planning example, the Product Owner brings the Sprint Goal for discussion with the team, updates the team on current state of the Product Backlog, provides additional information on Product Backlog items if needed, and helps select appropriate items for the Sprint Backlog. The Developers review the Sprint Goal and assess its achievability, estimate effort and complexity of work and select the Product Backlog items that they believe can be completed within a Sprint, and decompose these items into smaller tasks that will make it easier to track progress. The Scrum Master helps the team to come to an agreement on the Sprint Goal, keeps track of time, and facilitates the conversation using a variety of tools where necessary.

If you don’t have concrete actions each attendee needs to take during the meeting, maybe you have the wrong attendees. Or maybe you just want them to be informed. In this case, think again on whether they have to be informed in a meeting, or an email summary or a recording will suffice.

Ok, the last part of the attendee story is The HOW.

What I mean by that is quite simple: open conversation is not an appropriate way to conduct a productive meeting.

Basically, what I’m trying to say is that just asking a question into the meeting room and then letting anyone to jump in with their thoughts is not a proper way to facilitate any discussion, especially, in a group of 4 or more people.

You don’t have to have a workshop set up for every meeting, but you need to define how you are going to run it. And if your meetings tend to end up as an open discussion, you didn’t plan well.

The biggest offenders here, in my humble opinion, are the Sprint Reviews where after the team presents features they developed, they ask: “does anyone have any questions or concerns?”

I rarely hear any concrete questions from the stakeholders. And I can’t blame them.

Instead, what the team may do is prepare and run a quick assessment that asks specific questions around the feature, like: is it what you expected? if there were no constraints, what would you add, change, or remove? etc.

You need to have a plan for how you are going to drive the conversation during the meeting, what kind of tools and practices you are going to use to help collect and organize people’s ideas.

This concludes rule number one which says that any meeting must have a clear purpose which includes the why, the what, the who, and the how.

Rule number TWO: No preparation means no meeting

One of the biggest problems with most meetings is that everybody comes unprepared. Sure, no one ever has time to get ready for the meeting. But often attendees just don’t know what they need to prepare.

So that’s something that should be clearly stated in your agenda. Like, “please read this document before the meeting”, or “think about these questions and bring your answers in a written format”.

But let’s be honest, we are not really conditioned to do this in advance anyway. The student’s syndrome is real.

This means that your meeting must have some time set aside for that preparation. Set 10 or even 15 minutes at the beginning where everyone goes over the preparation tasks for the meeting. Whether it’s reading a document, or writing down some answers, or pulling some documents to share.

And no, going to grab a coffee is NOT part of the prep time. And answering emails is also NOT part of prep time. That should happen outside of the meeting.

And here’s a radical idea, if not everyone who is supposed to contribute is fully prepared to have the meeting, YOU CANCEL THE MEETING even if it has already started!

And now another radical idea, if you don’t know what people are supposed to prepare for the meeting, maybe your meeting purpose is unclear and you should work on it first, before sending the invite. supposed to prepare for the meeting, maybe your meeting purpose is unclear.

A good example of the preparation in the meeting is how they do it at Amazon

Several months ago I heard about this talk where Jeff Bezos shared how they run their leadership meetings at Amazon. And since then I was fascinated by it.

The gist of it is that every meeting starts with everyone silently reading a six-page meeting memo for about 30 minutes. The memo outlines the details of the topic and what needs to be discussed.

One of the reasons why they do it in the meeting is that we all know that we can bluff our way through the meeting as if we read that memo. So when we do it all together, there is nowhere to run.

This example shows not only the preparation happening during the meeting, but also the fact that someone had to spend time on writing this six-page memo, so they know for sure what is expected from it.

And this works really well with the next rule…

Rule number THREE: The work must happen IN the meeting

Most of the meetings I see end up with an action to meet again after some additional work is done by the attendees, like familiarizing themselves with the problem, connecting with someone, etc.

Rule number three simply says that “to have another meeting” is not a good enough output from any meeting. And, of course, I covered this in short in the What of the attendee story in rule number one.

This is where you see how all these rules are connected with each other. Because, the how the meeting is facilitated is also essential here.

When you have a clear output defined upfront and a clear way to drive attendees to achieve that outcome, the work will naturally happen during the meeting.

People often tend to put the work aside to do outside of the meeting, which kind of defeats the whole purpose. Why are we meeting then if not to work together on something? I could just send a request to do something via email otherwise.

Don’t be afraid to put the work-work as part of your meetings. Even if it requires some individual work. You can totally put 15 minutes in the middle of the meeting, where each person silently does what they need to, and then presents it to everyone else, which can be used for the next step of your meeting.

For example, in Sprint Planning, the Developers may want to each sit down with a specific Product Backlog item and write up the tasks individually. Great! Let’s do it while sitting in the same room (or the same call) because that’s why we are here anyway. And this way you have uninterrupted dedicated work time to do it.

And finally…

Rule number FOUR: The timebox IS the timebox

For the love of all things holy, please mind the timebox.

Have a timekeeper who WILL interrupt the conversation if needed to make sure everyone knows how much time is left before the end. This small interruption may be exactly what the team needs to get back on track.

In addition, put aside 10 minutes before the end of the meeting, to wrap up the conversation. Don’t leave it to the last minute where you have to rush to quickly summarize the meeting. Exactly 10 (or even 15) minutes before the end, just announce “We have 10 minutes left. It’s time to wrap up our meeting. Let’s create a summary of what we have accomplished”.

The team will get better at keeping their conversations within the timebox and you’ll get better at determining how much time is needed for different types of meetings. But this will ONLY happen if you apply the timebox rigorously.

Kind of like the Zoom Breakout Rooms. Even if you are in the middle of saying something, Zoom will kick you out into the main room. Yes, the first few times it’s annoying, but then you start paying attending to the timer and think about how you can share your ideas in a more compact way.

In conclusion…

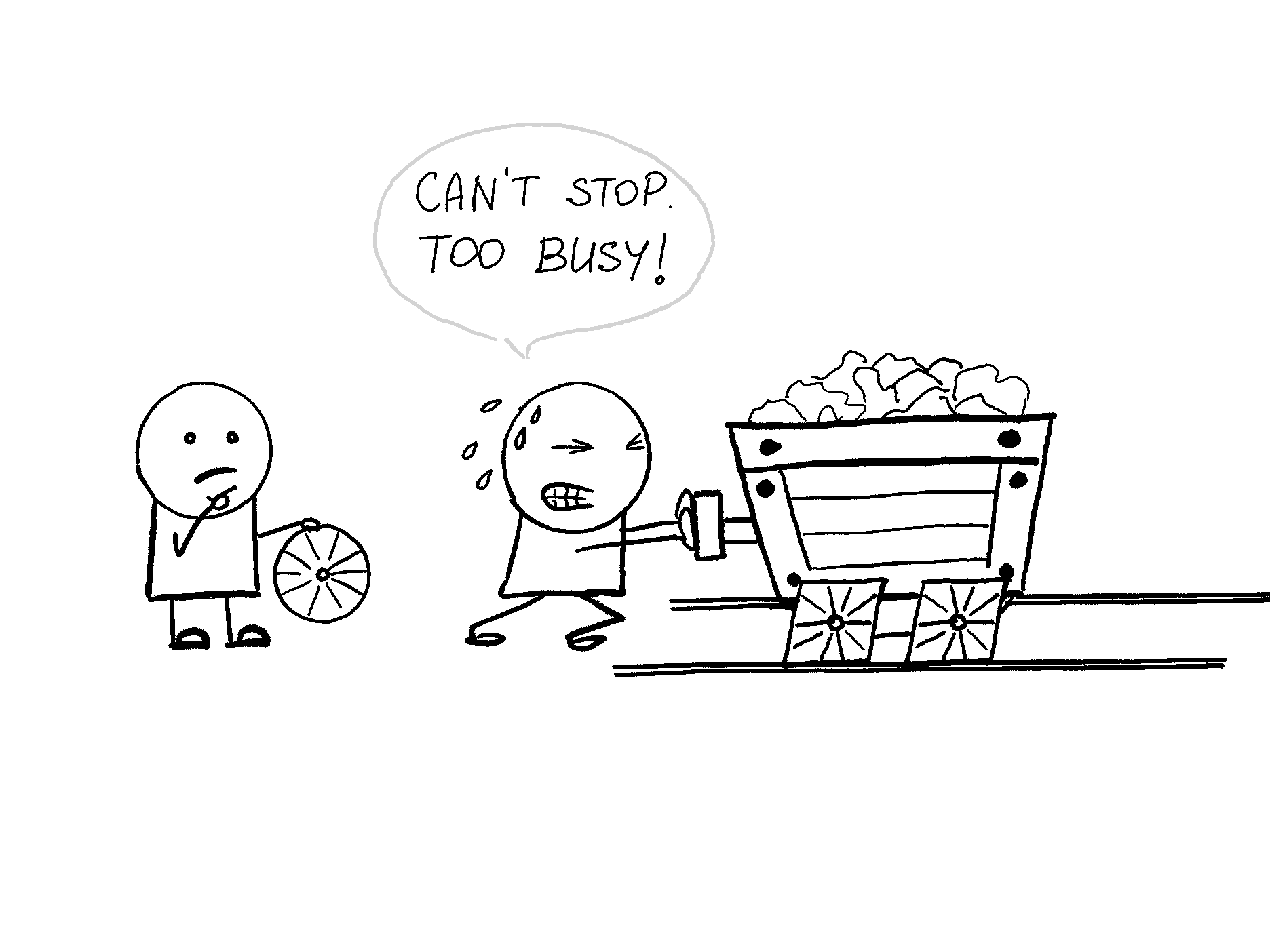

You might be thinking now: that’s A LOT to do before sending out or accepting a meeting invite. I don’t have time for that. And this is where I will show you my favorite picture of all time:

You may need to spend an extra 10 or 30 minutes now to figure out whether you need this meeting, but you will save potentially hours of your time in the future if you indeed don’t need this meeting. And if you do need this meeting, then you will be able to get the most out of it because you are fully prepared.

So STOP PUSHING THE CART WITH SQUARE WHEELS!

Anyway, that’s all I’ve got for this video. Thank you for watching and I’ll see you next time.

Check out my new online course created in collaboration with O’Reilly: